I've spent more hours than I could possibly imagine working on how to tell complex stories in exhibitions: how to layer a story, how to draw people in, how to include multiple perspectives, and most of all, how to make it something where people want to look, to read text labels, and something where visitors walk away talking about it. As those of you who also do this work know, it's really hard!

So when I see an exhibit that really is layered, that really draws people in, and is the first exhibit produced by an organization, I really want to share it.

This summer in Prague, I had a chance to see the exhibit "Sandarmokh – Where the Trees Have Faces" produced by Gulag.cz, an organization dedicated to documenting gulag sites of the former Soviet Union (and elsewhere). Gulag.cz was also the sponsor of a series of workshops I did in the Czech Republic this spring--their work is tremendous on many levels.

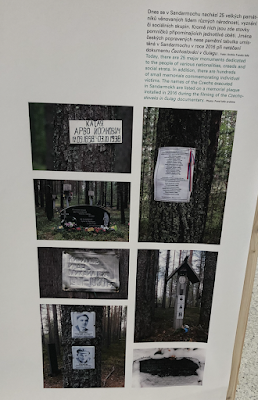

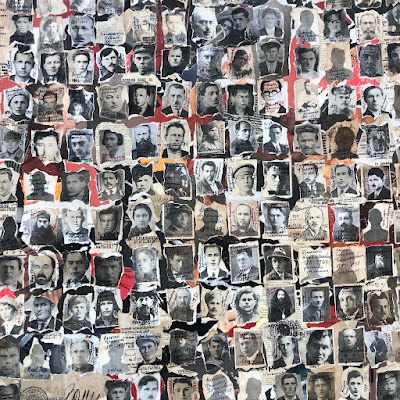

What were the layers? First, the exhibit is the story of Sandermokh, "a distant place in Russia’s Karelia, close to the Finnish border, and the scene of a massacre that was meant to be forgotten. As the Stalin repressions peaked in 1937–1938, more than 6,000 people of 56 nationalities were executed there. In addition to many Russians, Karelians, Finns, Ukrainians and the members of other European and Soviet nationalities."

Second, it's the story of historian Yuri Dmitriev from the Memorial association in Russia. Dmitriev and colleagues from the St. Petersburg Memorial office located Sandarmokh precisely in 1997, and they found and documented the names of the majority of those executed in the years that followed. But the official attitude of this work has changed greatly over the decades. Dmitriev was unjustly arrested, tried three times, and finally sentenced by the Russian Federation's Supreme Court. He is now serving a sentence of 15 years in a Russian penal colony.

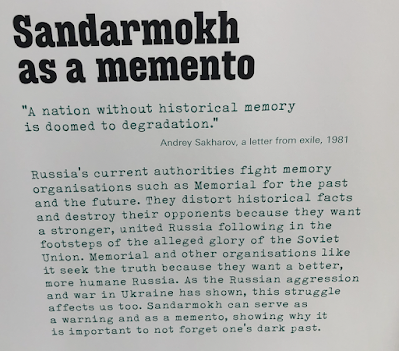

The third part of the story is that of Memorial International, a co-winner of this year's Nobel Peace Prize but also an organization that Russia considers a direct threat and which has faced repeated challenges to its work in Russia and has been disbanded there (though it continues its work elsewhere).

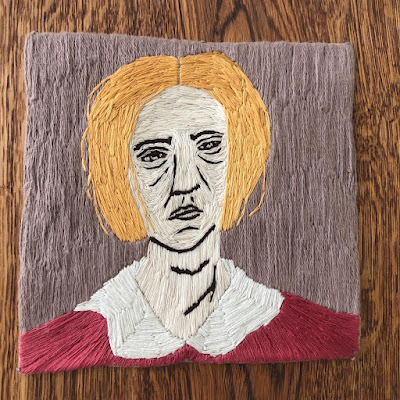

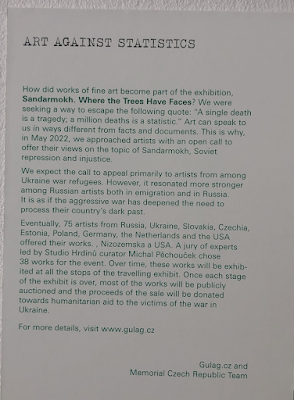

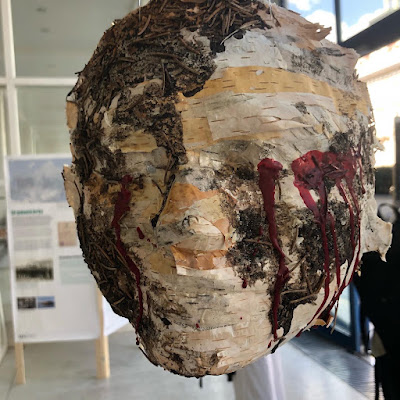

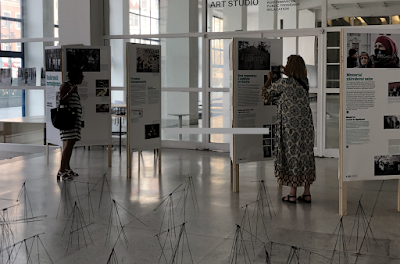

And the final part of the story: Gulag.cz issued an open call for art relating to the topic. More than seventy artists responded with an astonishing variety of work. When I saw the exhibit in Prague, just a few of the works were on exhibition, with others to be shown at each location. Once the tour is completed, the works will be auctioned off to benefit humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

What made all these stories, all these layers, work together in a small-scale panel exhibition when we often see layering attempts in big, expensive exhibits that fail? Here's the elements that I thin made it work.

People-centered. This exhibit is about people, about Yuri Dmitriev and his work, about others at Memorial, about those killed in the forest, and the artist statements give us an entirely other group of people to consider. No matter where you are in the exhibit, people are at the center. The goal of Stalin was to eliminate people and in every way, this exhibit reinforces that these people, and these stories matter. It's particularly relevant as Stalin's tools are returning every day in Ukraine.

Different ways of learning. You can look at the artwork--some of it easily accessible and some of it more challenging. You can read the labels. You can look at a recreation of Yuri's desk. You can look at historic photos of those who were killed and more recent, yet historic photos of memorial ceremonies at the site.

Really well-written labels. I was lucky enough to visit the exhibit with Stepan Cernousek and Petra Černoušková of Gulag.cz. When I mentioned how well-written--brief and compelling--the labels were, Stepan laughed and said, "oh, that was all Kristýna! She kept telling us that we had to use less text!" A big shout-out to Kristýna Pinkrová, a tremendous museum colleague who I also got to know this spring.

Simple, low-budget design. The exhibit is traveling, so the design needed to be affordable and adaptable to many different spaces. It was a modern, window-filled space in Prague and it looks like a vaulted brick-ceiling space in Brno. But the design works both places.

And lastly, and perhaps most importantly, tell stories that matter. There are important, vital stories to tell in every community, no matter where you are in the world. You don't need to do another display of wedding dresses or the chronological history of your town. If you don't think those stories exist, you aren't listening.

At the Prague opening, Dmitriev himself was able to speak by phone from the penal colony where he is currently unjustly incarcerated and delivered the following thoughts:

"I immensely appreciate your hard work which you do to preserve the memory. However, I think we've done less than we could. At least, those who were engaged in the preservation of memory in the Soviet Union and in Russia. Maybe that's why we live in such difficult times now. Complicated and tragic times. Nevertheless, I don't think we should give up for we must continue to deal with what we have dealt with, to talk about what has happened and what is happening now. For there is a direct connection between the past and the present. That's probably all I wanted to say to everyone here. Good luck.“

These are my own photos--you can see many more, and much better ones on Gulag.cz's site. Many, many thanks to Stepan, Petra, Kristýna, and all those who worked on the exhibition. I am so proud to know you and inspired by your work!

%20(1).jpg)